Thread of Art History: Transgression of Chinese Contemporary Art in the Sigg Collection

By Gu Zhenqing, Curator

Uli Sigg’s collection of Chinese art primarily focuses on the continuous art historical chronology from 1966 to today. The works highlight a half-century, beginning with the period prior to the emergence of Chinese contemporary art (1966-1978), its formative years (1979-1989), and its period of maturation and peak (1990s onwards).

From 1966 to the present, Chinese art has evolved through various movements. From the magnificent “Great Proletariat Cultural Revolution” art movement to the pursuit of freedom of the Star Art Movement, from the surge of the 85 New Wave Art movement to the Post-89 art in the 1990s, to the movement in the new century where Chinese contemporary art is forming indigenous value under the conditions of globalization and consumerism. Traces from the previous movements have guided every renewal and replacement in the artistic expression and implications of Chinese contemporary art.

I. Cultural Revolution Art (1966 – 1976)

“Cultural Revolution” Art generally refers to the political art from 1966 to 1976 made during the Cultural Revolution and the post-Cultural Revolution period from 1976 to 1978. The Great Proletariat Cultural Revolution completely subverted the past and criticized all traditional forms. Its effort of re-inventing the great uniform “Revolutionary Culture” collapsed the original art system of the seventeen years prior to the “cultural revolution”. The art field did not have power or standards, but the red, political public art movement became the mainstream and was widely popularized. The mass art movement brought numerous amateur artists to the creative front, allowing more people to pick up the paintbrush to form into creative brigade. The “sacred image” of Mao Zedong and formulaic figures of workers, farmers and soldiers were imitated and appropriated, which allowed numerous youths to participate in the art movement of the “cultural revolution” and to grasp the experience of “everyone is an artist”.

After 1970, young artists with training from art academies were drafted into creative groups in different cities and provinces nationwide and mostly created thematic oil paintings. With the encouragement of Mao’s wife, Jiang Qing, these youth discarded the rote creative style imported during the period of popularizing western painting techniques and Soviet art education model. Through their effort of infusing populism and Eastern/Western artistic traditions, they sought romanticism in their work and established a new national style in pursuit of beauty. The outcome of these efforts was a “cultural revolution style” oil paintings that are bold in composition and use of color. Chen Yanning’s Chairman Mao Visiting Guangdong Countryside, 1972 (image 2)is a typical example of this style.

image 2 Chen Yanning Chairman Mao Visit Guangdong Countryside, 1972, Oil on canvas, 172.5 x 294.5 cm

Although the artist attempts to render true emotions through realism, he is unable to depart from the representational mode of tall, large and wholesome figures. The idealized, stately figure of Mao Zedong contrasts with the surrounding masses, depicted a half a foot shorter. Chen formulates a theatrical composition of lesser hosts surrounding the guiding figure against a backdrop of a new prosperous and lively countryside. This new type of mainstream image highlights a tension in artistic representation. In Sun Guoqi and Zhang Hongzan’s Divert Water from the Milky Way (image 3),

image 3 Sun Guoqi & Zhang Hongzan Divert water from the milky way, 1973-1974, Oil on canvas, 180 x 310 cm

he artists’ subjective and romantic passions were expressed in a near-extreme surrealism, where the visual amalgamation of the figures and actions yield powerful visual tension. The artist renders perfect character on the workers’ faces through red colors and highlights. They differentiate and distinguish this style from the earlier Soviet creative model and trends by using the color characteristic of the so-called “Chinese style” oil painting of “red, light and bright”. The figures in Wu Yunhua’s From the Tiger’s Mouth (image 1) are not only composed as theatrical posing sculptures,

image 1 Wu Yunhua From the Tiger’s Mouth, 1971, Oil on canvas, 221 x 201 cm

but also display in a pyramid composition – a representation of Jiang Qing’s aesthetic principle of “model” figures. These are certainly the most art historically significant works from the “cultural revolution”. These works were exhibited in the 1972 national art exhibition to commemorate Mao Zedong’s 30 years of Talks on Art and Literature in Yan’an and in the 1974 National Art Exhibition to celebrate the 25th year of the founding of the People’s Republic of China, were made into millions of copies, and disseminated as part of the collective memory of the “cultural revolution”.

The important artistic phenomena unique to the historical period of the “cultural revolution” demonstrate that “cultural revolution” art is not simply a movement of cultural vandalism. As Mao’s principles of utilitarian art and mass art were accepted by the people, “cultural revolution” art formed aesthetic factors and rare cultural phenomena in art history, which had a great impact on the impetus of Chinese contemporary art. Until today, “cultural revolution” art is still part of the historical sources behind Chinese contemporary art and should not be overlooked. To a certain extent, the formation of the art structure in China today largely originates from “cultural revolution” art – thus art from the Cultural Revolution marks the incubating period of Chinese contemporary art.

II. Art in the Transitional Period (1979-1989)

In 1979, China began to reform and open-up to the world, with its market economy making substantial progress. Chinese society was on the fast lane of economic growth and social transformation.

In the art world, the national art exhibitions, under the official art association system, were still flooded with propaganda style artworks that illustrated grand narratives and conformed the mainstream art façade to ideology. Yet, the dominating political official art structure began to defrost. A number of traditional art and academic schools were revived and artworks emphasizing formal beauty, without highlighting political correctness, also began to emerge. Such “aberrant” artworks provoked wide discussions within the artistic mainstream. Yet the most radical rupture came from the bottom of the art world. In September 1979, the exhibition Star Art, initiated by young amateur artists, was displayed on the outer fence of the National Art Museum. The exhibition shocked the art community and officials closed it down after two days. The artworks on display appropriated and copied a number of modern representations from the west, through which to expose the dark side of society in their truthful attitude and to convey an inclination to liberalism and relatively individualistic aesthetic tastes. Wang Keping’s wooden sculpture Chain (image 5)was a significant piece from this exhibition.

image 5 Wang Keping Chain, 1979, Carved wood, 53 x 35 x 13.5 cm

It portrays a figure’s head in pain from being choked by a large hand. This Chinese figure without freedom of speech procured strong reactions from the public. Another member of the Star Art Group, Huang Rui’s work Yuanmingyuan (image 4) personified the objects of a landscape.

image 4 Huang Rui Yuan Ming Yuan 1979, Oil on canvas, 55 x 70 cm

The pillars and trees in the ruins of Yuanmingyuan were transformed into silhouettes of giant figures. Shadows of these figures leaning on each other are obvious appropriations of European cubism. Star Art strove for liberal creativity and freedom of expression and it not only marked the beginning of China’s avant-garde art, but also became a symbol of independent art exhibitions in China.

In 1980, Star Art Exhibition was held in the National Art Museum and was open to the public. Thereafter, the avant-garde artists in conceptual pursuit of contemporaneity, and who resisted traditional art and officially endorsed art, began to become an increasingly proactive artistic force in China. Creative movements of avant-garde artists profoundly impacted the formerly rigid ideology that was officially endorsed and brought forth various “aberrant” thoughts. The Chinese art world then established information sharing and communication with the international art world. The influx of contemporary art and culture from abroad instigated further significant changes in the Chinese artistic structure. However, in terms of creativity, the artists’ avant-garde explorations were still represented through their remedial experimentations on various Euro-American artistic trends. Wang Peng’s work 84-ink-5 (image 6) was the earliest performance art in China, in which he used ink to copy his body, and we find traces of Yves Klein’s influence.

image 6 Wang Peng 84-ink-5, 1984, Ink on paper, 68 x 106 cm

Yves Klein blue oil was replaced with Chinese traditional material, ink, and the “body measurement” of naked female models was also replaced with the body of the artist himself.

Ideological emancipation movements in the Chinese art world reached a climax in 1985 with the 85’ New Wave Art Movement. In fact, it was a stormy movement of cultural criticism and reform. Numerous young art groups nationwide initiated waves of art events and exhibitions. The bottom-up, anti-tradition, anti-mainstream position of collective resistance are superficially similar to art movement of the “Cultural Revolution” period, yet the objective was entirely different. The New Wave Art movement studied, appropriated and adopted the modern and contemporary art in Europe and America and it pursued individual freedom and cultural value of art. New Wave Art movement changed the monotonous condition of artistic utilitarianism and renewed and broadened people’s artistic vision, which lead the way to artistic diversity in China. A number of excellent artworks emerged out of the myriads of “improvisation” and student homework-art. Huang Yong-ping, a representative figure of the Xiamen Dada art group, emphasized uncertainty between Dadaism and game spirit. He dutifully effaced the meaning of painting by attempting to abstract various absolute truths and principles. He initiated the “paintings burning” incident, and invented a playful painting approach. In Six Small Turntables (image 10),

image 10 Huang Yong Ping Six Small Turntables, 1988, Mixed media, 50 x 40 x 16 cm

Huang installed six tables with written codes and by turning the tables determined the type of paint, composition, time frame to complete a “painting”. His usage of turntables emphasized spontaneity and coincidence to determine the artistic creation, which lead to a non-expression of subjective expression.

Some artists, such as Geng Jianyi and Zhang Peili in Hangzhou, were more interested in individual experience and the state of one’s existence. The exaggerated expressions and frozen laughing faces in Geng Jianyi’s oil painting The Second State (image 8) is a good example.

image 8 Geng Jianyi The Second Situation,1987, Oil on canvas, 4 paintings, 170 x 132 cm each

Set within large dimensions, these ferocious looking masks are estranged from the smiling faces on the bald heads floating against the black background. These pale and character-less smiles contrast with the smiles of optimism from the masses, and reflect the void in social consciousness of the masses. Geng Jianyi’s originality in these bald heads, large and smirking faces seems revealed an avant-garde characteristic that impacted a large number of artists thereafter in their paintings of “large head” portraits of the 1990s. In 1987, Zhang Peili portrayed a series of emotionless rubber gloves in his painting X? (image 9).

image 9 Zhang Peili X? Series: No.4, 1987, Oil on canvas, 180 x 200 cm

The images on the paintings were strictly imitations of the photograph taken of the object. These giant gloves are isolated from any specific background and take the central position visually as the protagonist of the work. Zhang Peili was especially interested in the symbolic meaning of the rubber gloves being between life and objects, as well as the conceptual value it embodies in different exhibition contexts. These meticulous imitations from photographs of the gloves were early explorations of conceptual art in China.

In 1989, the Shanghai artist Ding Yi painted an abstract painting Shizi (image 11) and began his decade long artistic career laboring over the spirit.

image 11 Ding Yi Shizi,1989, Oil on canvas, 50 x 60 cm

In order to testify whether the death of painting was a pseudo issue, since 1989, Ding Yi was determined to paint shizi (cross) on his paintings, displaying his consistent attitude treating painting shizi as a daily task to scrutinize. Every day, every hour, every time, almost the same cycle of hand labor is considered in Ding Yi’s perspective as the one and only way to exhaust time and life. Therefore, on the behavioral level, his painting strokes are comparable to ascetic practices. The spirit is abstracted from the repetitive motion of painting by which to explore one’s endless potential.

In February 1989, China Avant-Garde Exhibition was held at the National Art Museum of China – an exhibition considered as a conclusion of the 85 New Wave Art Movement that gathered avant-garde artists nationwide. Quite a number of artists are still passionate about collective memories and still adopt the grand narrative as a vehicle of expressing contemporary thoughts. Yet these artworks are still imitating European and American art historical classics in form and concept. Among them, there were also artists who were interested in exploring China’s own visual resources, looking at and extracting from the traditional and Mao era culture in order to establish contemporary art with Chinese characteristics. Xu Bing adopted the block characters of ancient Xixia, making a monumental work bound by the traditional thread method with unrecognizable characters Book from Heaven (image 72).

image 72 Xu Bing Book from the Sky, 1989, Wood cut, 4 volumes, 46 x 30 cm each

He highlights formal aesthetics, while rejecting the utilitarian principle of art endorsed officially. Among the participating artists, Wang Guangyi’s sensible foresight identifies and examines visual sources from the Mao era. His Mao Zedong series painting shown at the China Avant-Garde Exhibition implies a certain degree of cultural criticism. Red squares were drawn onto the standard portrait of Mao, which meticulously concealed the forbidden image of former political culture. These squares invariably symbolize a type of quantified logic, indicative of a reflection on politics and artistic form. Furthermore, this work provoked a string of discussions on the sacred portrait of the leader, while catalyzed the visual hype of Mao Zedong figure in the 1990s (image 7).

image 7 Wang Guangyi Mao Zedong: Red Grid No.2, 1988, Oil on canvas, 150 x 130 cm

In 1989, artists Gu Dexin, Huang Yong-ping and Yang Jiecang participated in the Magicien de la Terre exhibition at the Centre de Pompidou and Cite de Science de la Villette, curated by Jean-Hubert Martin. It was the first international exhibition where contemporary Chinese artists were invited to participate. Thereafter, these artists were passively involved in an international contemporary art scene already prominent in Europe and America for about a century.

The period from 1979 to 1989 was a budding era in Chinese contemporary art. The modern, contemporary and classical art issues unraveled in non-chronological order that flooded into the Chinese art world. They interacted with existing artistic ideology and overlapped with establishing a new, yet transitional artistic structure. It was period of transition in contemporary Chinese art, during which art movements built solid foundations for its later developments.

III. Chinese Contemporary Art in the 1990s

A

In the early 1990s, social transitions in China accelerated while people’s political passion waned, instead consumerism began to plant its seeds in people’s mind. Also contemporary Chinese art was undergoing drastic changes. Independent artists began to emerge, who were driven to search for self-value and reinvention as they were confronted with China’s unique national condition and unrelenting ideological context. At the same time, the two most remarkable artistic phenomena were the Yuanmingyuan artists’ village and the trend of political pop based on artistic modes from the “cultural revolution”.

Around 1990, Fang Lijun’s remarkable contribution to the contemporary Chinese art history is not only the rebellious shaved head portraits (image 22),

image 22 Fang Lijun Untitled, 1995, Oil on canvas, 250 x 180 cm

but also the formation of a professional artist identity. At the time, along with Yue Minjun, Yang Shaobin, he and many artists rented rooms for studios from the Yuanmingyuan villagers and began to paint and sell their works for survival. The Yuanmingyuan Artists Village became well-known because they were Chinese artists who abandoned the iron-bowl and indiscriminate egalitarianism in the vast and uniform art system. This group of artists was the first to become financially independent, which earned them a certain degree of freedom in their dignity and creativity under the pressure of official ideology. Fang Lijun and Liu Wei held exhibitions in 1991. Their oil paintings portrayed themselves and the young friends around them. Their smirks or unsettling facial expressions present a cynicism and skepticism of reality and they belittle the mainstream as they awake from their utopian dream. These works embody the psychological depth of the artists and critic Li Xianting defined their work as Cynical Realism. Among the artists of Yuanmingyuan Artists Village, individual consciousness was budding. Their artistic individualism was brought into play and made widely known through personal narratives, through their individual artistic language. The artists were dedicated to breaking away from collective consciousness in order to enter an era of individual existence and thinking. Therefore, the context for Chinese contemporary art also began to undergo tremendous transformation. Blossoming in the wilderness, for these artists outside the system, the main principle was of survival and cultural strategy. Consequently, a shift formed among Chinese artists. They revised the social status of contemporary art, but also paved a path for the self-invention of star artists in the future.

Meanwhile, other artists wantonly copied, appropriated and deconstructed artistic modes of the “cultural revolution”. They treated the “cultural revolution” visual resources as the only cultural heritage to reflect upon and satirized the despotic era. Wang Lin and other critics proposed “post-89 art” concepts to describe the creative condition at the time. Wang Guangyi was the first to set this trend. His Great Criticism series of oil paintings, started in 1991, was one of the remarkable works at the beginning of “Post-89 Art”. He purposefully appropriated the popular Cultural Revolution motifs of workers, farmers and soldiers and proportionally enlarged them on canvas as high-resolution oil painting images. Yet the focus of criticism was changed to Coca Cola, Chanel and other international brands (image 62).

image 62

Wang Guangyi Chanel No.5,2001,

Oil on canvas, 300 x 400 cm (2 panels); 2 fibreglass sculptures, 180 x 140 x 80 cm each

Wang Guangyi’s repeated use of the collective memory motifs of the Cultural Revolution motifs was, in fact, also an appropriation of Euro-American’s artists’ practice of enterprising self-images. Based on his works, critic Li Xianting named this trend as “political pop”. Moreover, with Wang Guangyi’s persistence, he became the first to establish classic image motifs in contemporary Chinese art.

Shortly thereafter, the so-called “political pop” painting style reached its height. Yu Youhan’s and Li Shan’s oil paintings were inspired by the image of Mao. For instance, Li Shan’s Rouge-Flower series (image 37) replicated repetitively salon style photographic portraiture that was popularized during the Yan’an period.

image 37 Li Shan Rouge–Flower, 1995, Oil on canvas, 130 x 186 cm

He added the dangling flower detail to emphasize its sacredness as a portrait of a Buddha. Yu Youhan’s oil painting, Chairman Mao in Discussion with Peasants from Shaoshan (image 80),

image 80

Yu Youhan Chairman Mao in Discussion with the Peasants of Shaoshan, 1999, Oil on canvas, 200 x 150 cm

literally selects and edits a photograph of Mao from the Cultural Revolution. The image was meticulously collaged with flower print fabric motifs popular in Chinese folk culture. Symbols and visual resources from the “Cultural Revolution” were gradually satirized and criticized. Feng Mengbo used digital technology to distinctively juxtapose Mao and contemporary urban cartoon characters in his electronic game art Taxi! Taxi! (image 24).

image 24 Feng Mengbo Taxi!Taxi! 1994, Oil on canvas, 100 x 354 cm

The image of Mao has been ineffaceable over the years. The image of Mao in military costume that has been mass produced are reflecting in artists’ work and attest to artists’ familiarity and subconscious acceptance. Xu Yihui’s Untitled (Red Book)(image74) used ceramic to remake Mao’s Quotes that was ubiquitous during the Cultural Revolution.

image74 Xu Yihui Untitled (Red Books) , 1999, Porcelain, A set of 45 pieces, Dimensions variable

The traces of deformation and churning of the red books during baking of the ceramic books were purposefully kept by the artist in order to suggest the event of book burning. Perhaps, the artist’s malicious imitation in using stereotypical visual motifs from the Cultural Revolution was not only a critique on the centralized art structure under a despotic society, but also exposes his reminiscent nostalgia and admiration of the dogmatic formulaic artistic style. Sui Jianguo’s Legacy Mantle (image 59) alludes to specific figures attached to the “national attire”.

image 59 Sui Jianguo Legacy Mantle, 1999, Aluminium, 240 x 190 x 30 cm

Sun Yatsun suit associated with Mao Zedong is made into a hollow sculpture. It is a work that both enlarged the actual object that seems both familiar and novel, as well as positioned the artwork as China’s new cultural canonical form in a period of transition.

1993 was the year when contemporary Chinese art made substantial contact with the mainstream international contemporary art scene. Two exhibitions were especially remarkable. The first was the Post-89 New Art from China curated by Li Xianting and Johnson Chang held at the Hong Kong Art Center with participating artists Fang Lijun, Zhang Xiaogang and etc. The other was the 45th Venice Biennale’s thematic exhibition Road to the Orient curated by Achille Bonito Oliva, who invited 14 Chinese artists, Wang Guangyi, Zhang Peili, Geng Jianyi, Xu Bing, Liu Wei, Fang Lijun, Feng Mengbo, Yu Youhan, Li Shan and others. Contemporary Chinese art became known to the European and American art worlds. Although their artworks were formally diverse, but their expressions were quite literal and the contents were closely tied to China’s condition. Therefore, soon, contemporary Chinese art ignited the ‘China fever’ in the Euro-American art world. Chinese contemporary art as a visual art form became a window for European and American societies to learn about China’s reality and investigate Chinese mentality. In 1994, Fang Lijun, Liu Wei and other Chinese artists were invited to participate in the Sao Paolo Biennale. Thereafter, Chinese artists frequented various international art biennales in Europe and America, and there was closer and more frequent interaction between these two art worlds – the intangible yet hindering barrier, separating China from the world was pierced. The tumultuous growth of contemporary art in China began to receive valuable support from the international society. Some Chinese artists became more willing to “connect internationally” in forming a cultural strategy that emphasized collaborating with the outside world.

In the 1990s, the other tendency in contemporary painting was based on the cultural response to the reality of everyday life and historical images. Zhang Xiaogang’s Bloodline series oil painting (image 85) originated from a coincidental discovery in 1994 of his parent’s old photographs from the Cultural Revolution.

image 85 Zhang Xiaogang Bloodline Series, 1998, Oil on canvas, 147 x 189 cm

Therefore, using bloodline as a thread, family portraits became the creative and visual blueprint for Zhang Xiaogang. His images appropriated the carbon rubbing approach used in black and white photographs adopted from the painters of folk portraitures. The solemn expressions, gazing stares, and sorrowful tones of the portraits easily awake the historical memories buried in the hearts of the masses. These images are visually penetrating. Zhang Xiaogang re-explores old photographs from the Cultural Revolution period and, to a certain degree, also planted seeds in the catalysis of the “old photo” trend in the art fields in China after 1995.

Fang Lijun created the shaved head self-portrait to express his rebellious spirit. Zhang Xiaogang’s introspective reflection of his bloodline family is a saturation of collective memories. Yue Minjun’s laughing self-portrait became an eternal motif that replaced all other characters in his paintings. Similar to Wang Guangyi who overbearingly adopted Cultural Revolution figures of the workers, peasants and soldiers motifs as his own artistic symbols which led to the origin of the individualistic art in the “post-89” painting style, these three artists different but coincidental systems of representation displayed self awareness and individual freedom through personal narrative. However, the motifs in their artworks became increasingly systematized and symbolic. Also, the artists’ insurmountable self-repetition set the trend in post-89 painting as a stylistic movement of visual restoration. Such painting style of the “post-89” in the decade after 1995 solicited a group of artists outside of the system who followed these trends and the art market hype. Post 2000, the exaggerated large head portraits and big faces paintings were exceedingly popularity, when in fact its avant-garde spirit had already waned.

B

In 1994, the contrast between China’s economic reform and market freedom and the tightening of policies in it political despotism expanded drastically. Beijing’s other artist village, the “East Village” was inhabited with artists like Zhang Huan, Ma Liuming, Wang Jin, Zhu Fadong, Zhuang Hui, Cang Xin and others. Ma Liuming was arrested and detained for two months for Fen – Ma Liuming’s Lunch, a performance piece he carried out in the nude containing sexual overtones. Soon, officials forced evictions and sealed the East Village. Ma Liuming used his individual right of his body, but officials aggressively intervened and forced him into helpless experiences. Thereafter, the artist realized a series of performances interacting and photographing with the audience while nude at various international art exhibitions (image 49).

image 49 Ma Liuming Fen-Ma Liuming in Geneva 1999 Switzerland, 1999, B/W photo, 127 x 267 cm

The artist also took sleeping pills to sleep in his performance in order to lose self-consciousness so that his body could be at the disposal of or photographed by the audience.

In April 1995, Beijing’s Yuanmingyuan artist village was officially closed off and all artists from the village were evicted and dispersed.

At the time, Zhang Huan and 10 other artists living in the East village felt a sense of crisis and collectively performed Adding one meter to a nameless mountain—they piled on top of each other according to body weight. It was a work that projected the living conditions of Chinese contemporary artists, who emphasized introspective views and the deepening of personal experiences. At the same time, using their last resource, their bodies, artists resist and struggle against their hopeless reality.

Also in 1995, like Fang Lijun, who moved to Xiaopu village in Songzhuang, Tongxian, an eastern suburb of Beijing, some key artists from the Yuanmingyuan artist village, as well as a large number of artists from other provinces, began to flood into Songzhuang. They rented houses from the villagers and made artworks, making the area into Songzhuang art district. Like other painters, Yue Minjun had built his studio in Songzhuang and painted Everybody Connects to Everybody (image 81).

image 81 Yue Min Jun Everybody Connects to Everybody, 1997, Oil on canvas, 127 x 526 cm

The exaggerated laughing self-portraits lined up one after another and hugging each other seems to be a metaphor for the close relationships among artists, who relied on each other while sharing the pressure of survival.

In and around the city of Beijing, native Beijing artists lived and worked relatively independently. For instance, Gu Dexin, Li Yongbin, Zhu Jia, Song Dong and Yin Xiuzhen, as well as the artist couple, Wang Gongxin and Lin Tianmiao, have already been proactive in the contemporary art scene for many years and experimented with various medium and forms. Making art was already their way of life. On the one hand, expressing their artistic position and attitude is their approach to constantly confirm their identities; on the other hand they continue to explore and search for a space of survival for contemporary art within the everyday reality of Chinese society and attempt to find local and normalized contemporary art. Song Dong’s 1996 performance, Breathing (image 58) was an outstanding work among his Beijing peers.

image 58 Song Dong Breathing, 1996, 2 photos, Colour photo, 120 x 180 cm each

The artist performed the winter game of breathing into the cold at public places such as Tian’anmen Square and the frozen lake surface in Houhai. Song Dong crawled on the ground for 40 minutes, exhaling constantly onto the ground, which eventually created a piece of ice on the ground. The same actions done on an ice surface created no change. Song Dong’s approach of his own experience with the world is quite humble. Breathing allowed the artist’s carbon dioxide exhalations to transform into a type of energy and personal traces. However, it might or might not change the world. Song Dong’s experience of the climate in his environment was symbolic of the social and political context in China. If the artist’s day to day work is to be converted into value, external social changes taking place need to be examined, as well as a type of strategy needs to be coordinated with the right time and right place.

In other provinces, some artists have formed into groups to collaborate on everyday works and exhibitions. Among them, the most well known is the “Big Elephant Tail” group found in 1991 by Chen Shaoxiong, Lin Yilin, Xu Tan, and Liang Juhui, influenced by Fluxus from Europe to promote and seek for visual experiences from newer methodologies. The members of the group collaborated and exhibited together for over a decade. For instance, Chen Shaoxiong’s Sight Adjuster III (image 18).

image 18 Chen Shaoxiong Sight Adjuster Ⅲ, 1996, Video installation, Dimensions variable

Living in the Pearl River Delta region, the forefront of China’s economic refoms, rapid social transformations and highly inflated urban space are part of their everyday experience. Confronted with the exciting reality of renewal, they have made a series of immediate reactions and responses, passively or actively, in attempt to intervene the progress of social transformation. Lin Yilin’s Safely Manuvering over Linhe Road (image 94) directly involves art into social orders to present the constantly progressing experience of reality through orderly or chaotic artificial rules.

image 94

Lin Yilin Safely Maneuvering Across Lin He Road, 1995,

Single channel video, Sound, Color, 36 minutes 45 seconds, Loop

In the mid 1990s, the artists who immigrated to Paris, such as Chen Zhen, Huang Yong-ping, Wang Du, Yan Peiming, and Yang Jiecang, and artists who now live in New York, such as Cai Guo-qiang, Xu Bing, and Gu Wenda, were becoming increasingly active and displayed their Chinese identities in international exhibitions. Many have returned to China to realize their art projects. Their life experiences in Europe and American made them more aware of cultural strategy and approaches to international operations. They are keen on explaining the meaning of art in ways westerners would comprehend and accept. Moreover, their works have intentionally or unintentionally revealed cultural symbols of Chinese tradition or oriental characteristics, such as Huang Yong-ping’s Pharmacy (image 33) and Gu Wenda’s Myths of Lost Dynasties (image 26).

image 33 Huang Yong Ping Pharmacy, 1995 – 1997, Mixed media, 256 x 645 x 262 cm

image 26 Gu Wenda Myths of Lost Dynasties, 1999, Ink on paper, 310 x 205 cm

Also, artists like Wang Du were more interested in playing with his international identities and banter on international issues, as seen in his 1998 work Strategie en Chambre (image 61).

image 61 Wang Du Strategie en Chambre,1998, Mixed media installation, Dimensions variable

These artists often appeared in the most respected international art events, through which Chinese art gained international reputation.

The major changes in international politics, economy, and culture after the Cold War also contributed to “China fever” sweeping the international art world. On the one hand, China’s accelerated economic reforms made economic interactions with Europe and America more frequent, thus China could no longer be bypassed and, by the same token, its cultural and artistic exchanges could not be overlooked. On the other hand, the visual heritage of the long historical traditions and socialist culture found in Chinese contemporary art was the different and exotic quality western aesthetics yearned for. In fact, there was also a need for Euro-American societies to bring Chinese contemporary art into the global structure. Therefore, as critics of imitation in Chinese contemporary art grew fierce, Euro-American societies tried to accept Chinese trends of “political pop” and kitsch art. For some, the so-called Chinese contemporary art was like fast food of political culture. This fast food attained new height in the Mao 100 exhibition in New York in 1994. Other European and American art museums and alternative art spaces in the meanwhile held quality group exhibitions by contemporary Chinese artists, for instance, Another Long March in Brada, The Netherlands in 1997. From these exhibitions, those interested in contemporary Chinese art from Europe and America began to recognized the unique value and implication of the artworks and began to research the underlying ideas, concepts, methodologies artists adopted, as well as the differences in developmental logic and chronology under China’s unique context. Among them, Hans Van Dijk, Karen Smith, Lorenz Hebling, Uli Sigg and Guy and Miriam Ullens have been long-term supporters over the years, and eventually became known as the “foreign” promoters of Chinese contemporary art. In 1995, Uli Sigg founded the Sigg collection, a special collection researching Chinese contemporary art, and established the Contemporary Chinese Art Award (CCAA) – an award that has gain respect through its focused and expertise research. This collection and award established a high standard that has propelled creative momentum in exhibitions and promotions of Chinese contemporary Artists.

C

Besides the popular thread in avant-garde art in the 1990s, there were also artists like Qiu Shihua, Shang Yang, Chen Guangwu, Ai Weiwei and Qiu Zhijie who were independent in mind and action. They focused on reorganizing and consolidating the essence of traditional Chinese art from a contemporary art position. They built art cases in the formation of expressing logic freely. Although these cases were suspended beyond the waves of the avant-garde, their criticism was heated with regards to rejecting the rigid and arbitrary meaning of realist models. The free expression of their soul and of the world around them related to China’s traditional heritage, revealing another type of contemporaneity with traces of Chinese traditional thoughts. Ai Weiwei’s Whitewash (image 12) from 1995 to 2000 whitewashed traditional color pottery – a crude act that seemed to negate the existing aesthetic order.

image 12

Ai Weiwei Whitewash, 1995-2000, 132 neolithic vases, industrial paint, Dimensions variable

As the object was in fact concealing and rejecting the aesthetic and values formally attached to itself. He restores and emancipates these objects from these common structures in order to show its original properties. Ai Weiwei’s expertise posits on critiquing and breaking free from set logical structures. Ai deconstructed ancient furniture, or even ancient architectural structures symbolic of traditional aesthetic order, then reconstructs and structures according to his personal visual experience. Artwork like Fragments (image 13) demonstrates his noncompliance to rules,

image 13 Ai Weiwei Fragments, 2005, Iron wood, Dimensions variable

using parameters beyond common rules to deconstruct obstacles and differences in cultural exchanges. Qiu Zhijie’s repetitive practice of calligraphy eventually fills a blank piece of rice paper entirely black in the performance Copying the preface of the Orchid Pavillion 1000 times (image 53).

image 53 Qiu Zhijie Copying the Preface to the Orchid’s Pavilion 1000 Times,

1990-1995, Digital print ink, A set of 5 parts, 106 x 55 cm each and DVD

He obliterates the content and formal significance of the artwork. This approach highlights Qiu’s concepts and is synonymous to Ai Weiwei’s whitewashed potteries.

In fact, Chinese contemporary painting in the mid 1990s shifted conceptually toward the possibilities of the individual. At the time, it was easy for artist in the plastic arts to respond to, to impact or even to rejuvenate the public’s aesthetic interest. Thus those with overall personal styles in their images and forms were favored under the rule of “visual priority” during that unique era, and were considered as an isolated generation and local façade of Chinese contemporary art history. Nevertheless, most painters of Chinese avant-garde art adopted the model of thinking in art socialism and the cultural path of traditional concepts. However, Ding Yi, Wang Xingwei, Zhou Tiehai and others submerged in the art world persevered in their works and foreshadowed the prospect of conceptual painting in China.

Under the renewal of conceptual painting, Wang Xingwei’s personal approach to re-comb art history was perceptive in China. In 1993, Wang Xingwei painted a series of oil paintings consisting only of himself and his girlfriend in a fashion that rejected techniques and classical aesthetics, as seen in Untitled (Munch) (image 66),

image 66 Wang Xingwei Untitled (Munch), 1993-1995, Oil on canvas, 180 x 240 cm

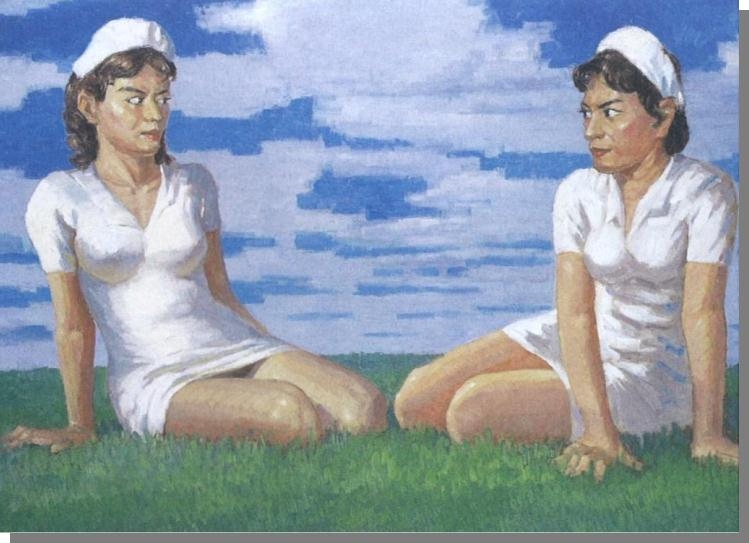

First Light and etc. The background of the painting appropriates Munch’s Scream and other classic paintings from European and American art history. Without any exceptions, the figures all face the disappearing point of the horizon and are immersed in a picturesque background. Thereafter, through painting, he began to unfold, probe into and reflect on the heritage of images in art history by embedding himself. The pursuit for the existence of painting led Wang Xingwei to augment his skeptical attitude towards history and form an artistic consciousness. Wang Xingwei enters the visual elements of the stage, costume, props, animals or self-portrait in a series of metaphors, symbols and satire to revise, maneuver and recreate the classic images of European and American masters. Thereafter, he even attempted to edit popular cartoon images from 1980s China, while revising his existing works. Untitled (Two Nurses) (image 67)

image 67 Wang Xingwei Untitled (Two Nurses), 2005, Oil on canvas, 107 x 154 cm

portrays two nurses staring ferociously. They have appeared in various paintings in different years and different styles. Regardless of his changing painting style, Wang Xingwei follows a certain pattern. He is fixated on the conceptual issues of painting in order to achieve a quality in his painting that is both implicit and introspective while revealing a free-spirited cultural confidence. Therefore, he was one of the earliest artists who was willing to abandon symbols and logo-like motifs in their paintings. A decade later, many Chinese artists began to revise classic paintings from European and American art history with their own personal style and motifs. The logical starting point on this thought is that Wang Xingwei’s exemplary actions has far exceeded the effortless aspirations of American artist Mark Tansey

In 1994, Zhou Tiehai concluded that former artists had already resolved common painting language and ontological issues. To continue painting by oneself is only to meaninglessly pursue hand painted brushstrokes and texture. Therefore, he entirely abandoned the creative model of painting by himself and turned to politicizing art history, the contemporary art system and the context in which cultural exchange between China and the West takes place – his identity completely changed from being a painter to a conceptual artist. Creatively speaking, he came up with ideas and inspiration and then engaged others to paint it. He then approved of the work and marketed it. His creative key is to use others’ hand to paint the image in his mind. Over time, he also got used to examining himself through the perspective of others. This dichotomous way of thinking practiced over time allowed Zhou Tiehai to assess Chinese symbols in the eyes of the Europeans and Americans, as well as the examine the Western objects and styles that the Chinese admire. Zhou Tiehai’s Press Conference 3 in 1996 fictionalized a scenario of himself as a successful person giving a speech, by which to deride and satirize the power of discourse in reality. As an “underground” artist, he conspicuously exemplified the value of self-centeredness and challenged not only the monopolized rights of art by the Chinese official, but also the comparable yet profit-seeking context of the international art system.

D

Around the second half of 1996, distinct and mature conceptual photography began to emerge in contemporary Chinese art. Many avant-garde artists picked up the camera and used photography as a medium to express their ideas. Soon, the photography world became active. Since 1996, staged photography with Cultural Revolution themes appeared frequently. Wang Jinsong’s Standard Family (image 64) and Zhuang Hui’s large dimension group photographs (image 91) are the earliest examples.

image 64 Wang Jinsong Standard family, 1996, Colour photo, A set of 200 pieces, 19 x 25 cm each

image 91

Zhuang Hui PLA Regiment 5141, Fourth Artillery Squadron, 23. Juni 1997, 1997, B/W print, 101 x 608 cm

Wang Jinsong used students enrolled in schools as a common thread and photographed over 200 three-members family portraits. In the photographs, the child takes the central position in the one-child family structure and clearly hints at the social issues that stem from this policy. Group photographs, bound by a system saturated over time, often transcend functions of documentation and commemoration and becomes illustrations for the spiritual impression of humanity with social and historical meanings. This is key for Wang Jinsong use of identity to examine social issues and for Zhuang Hui’s original inspiration in creating new group photos. From October 1996 to 1997, Zhuang Hui purposefully photographed 12 large groups in 1960s style. The social capacity of Zhuang Hui’s work is enormous and to use this scale to mobilize social resources in the context of a market economy undoubtedly requires dogged determination, as well as dynamic on-site operation and negotiation skills. Through the photographing process, symbols of collective spirit in the historical sense suddenly transformed into the materialized outcome of the artist’s creative intent. An artist stands quietly off to the side of the group being photographed, like an aberrant symbol inlaid into history, who symbolizes the further expansion of the creative boundary in contemporary Chinese art. Hai Bo’s 1999 They Recorded for the Future (image 27) presents comparative past and present diptychs of the same person. This work is reserved, tame and controlled to express the relationship between the Cultural Revolution and modern day living. It testifies to the unrelenting passing of time, invoking the bitter taste of life and the power of the human spirit.

image27

Hai Bo They Recorded for the Future (16 Women) , 1999, Colour and B/W photo, 2 photos, 103 x 308 cm each

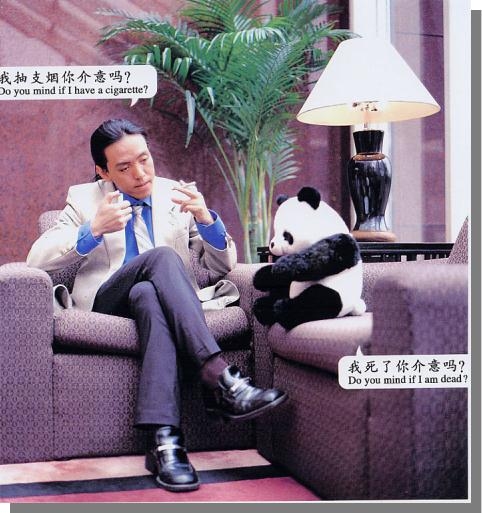

At the end of the 1990s contemporary photography revealed its diversity in its development in China. Started in 1999, Zhao Bandi and Panda (image 86) was a series of photographs Zhao Bandi executed in the style of public announcement, effectively binding himself with the symbolic meaning of the panda promoted through various public context and media. Zhao Bandi broke out from the self-secluded circle of the contemporary artists and imitated the star discovery system of the entertainment business. He collaborated with various social resources to purposefully create a rate of exposure. Zhao Bandi’s active marketing of his image was an earlier case of contemporary Chinese art intervening into social and public context.

image 86

Zhao Bandi Zhao Bandi And the Panda, 1999, Laser print, a set of 9 pieces, 128 x 145 cm each

Around 1999, artist Hong Lei (image 30), Huang Yan (image 32) and Wang Qingsong used photography to revisit Classical Chinese paintings. They used contemporary aesthetic concepts to transform and replace the original meanings of traditional images, which produced a differentiated and displaced visual impact.

image 30

Hong Lei After the Song Dynasty Painting Quail and Autumn Chrysanthemum by Li Zhongang / Lotus, 1998,

Colour photo, 102 cm diameter each

image 32 Huang Yan Chinese landscape: Tattoo No. 6, 1999, Chromogenic print, 50 x 61 cm (total 5 photos)

At the end of 1990s, as the public interaction with art overseas developed, Chinese artists had more frequent exposure to western contemporary art, and were more inclined to adopt photography, video, installation and performance art as their medium of artistic expression. Their search for spirit and experience of contemporaneity formed into a unique landscape of independent fighters. Chinese artists began to emphasize professionalism, expertise in their own creative domain; moreover making in-depth explorations on specific media. In 1997, artist Wang Jianwei and Feng Mengbo participated in the 10th Kassel Documenta exhibiting unique video and multi-media artworks. However, within the Chinese context, their pioneering artistic conscience became a true attack to the Chinese art status bound by its system and ideology.

Independent curators and the exhibitions they curate began to emerge. Although contemporary art exhibitions are still considered underground or semi-underground in Chinese social life, exhibitions have captured the great participatory enthusiasm of many young artists. The curator’s work connects the artist in different ways and provides an academic atmosphere for discussion and exchange. Young artists groups emerged sporadically throughout Beijing, Shanghai and Guangzhou. These groups no longer have specific manifestos or names, and the goal to gather are realized through collectively organized exhibitions. In 1999, independent exhibitions became more frequent. Among them, the group exhibitions Post Sense and Sensibility curated by Qiu Zhijie is an important example. The young participating artists later became the most active avant-garde artists in the new millennium.

In 1999, curator Harold Szeeman invited Ai Weiwei, Ma Liuming, Wang Xingwei, Zhuang Hui, Lu Hao, Wang Jin, Liang Juji, Zhou Tiehai, Xie Nanxing, Chen Zhen, Wang Du, Cai Guo-qiang, Zhang Hui, Zhao Bandi, Qiu Shihua, Ding Yi and others, a total of nearly 20 Chinese artists to the 48th Venice Biennale. The number of China’s participating artists caught the attention of international media and audience. Many believed that Chinese artists showed great potential and vigor. They were not only a new force that could not be overlooked in the progress of the globalization of art, but also provided a different path to the future in the logic of western art development.

IV. Chinese contemporary art in the new Millennium

In 2000, China established bilateral agreements with many WTO nations and the country launched itself into the WTO system. In 2001, China formally entered the WTO – marking China’s official entrance into globalized economy. Thereafter, the rise of China became a global topic.

2000 was also the year when Chinese contemporary art legitimately entered the domestic public sphere. It was also a year when it entered cultural globalization on the international stage. Independent curators were especially active in 2000. They applied for legal approvals for independent exhibitions they curated – these types of exhibitions, in the past, would have often taken place underground or within a small, internal circle. However, the curators were persistent on showing their exhibition directly to the public. Under official unannounced permission, independently curated exhibitions began to gain scale and influence. Among them, Infatuation on pain curated by Li Xianting, Men and Animals curated by Gu Zhenqing, Fuckoff curated by Ai Weiwei and Feng Boyi were some of the independent exhibitions from that time. In 2000, the contemporary art world was surging forward vigorously and received a tremendous social response. Contemporary art became a popular and conceptual term that the Chinese public was familiar with and disputed over. The works of Xiao Yu, Sun Yuan & Peng Yu, Zhu Yu, Qin Ga and other challenged traditional and social taboos by using animals and cadavers as their materials and using methods that were visually violent and shocked the public. He Yuchang and Wu Gaozhong used their own bodies in the extreme to represent certain social meanings through these performance art – these artworks boosted public attention to this field. Although contemporary art might still seem sensational, the events became social and public and could no longer be concealed or contained. Independent curators or self-initiated large-scale artistic dynamics occurred frequently with independent exhibitions. At the time, other than the very few radical exhibitions that were closed down, most independent art exhibitions gained legal standing indirectly. These exhibitions welcomed a more and more educated audience and contemporary art quickly became socially accepted.

On the other hand, the state-run Shanghai museum invited international curator Hou Hanru to organize a true international event – The Third Shanghai Biennale. It was an event that caught the attention of the international art circle. An international audience had the opportunity to appreciate an international biennale on Chinese soil. Meanwhile, this event offered other independent curators to present a series of satellite exhibitions during the biennale period. Allowing artworks by Chinese artists to be publicly shown to an international audience marked Chinese contemporary art exiting an ideological fortress and stepping into a globalized society. In 2000, artist Yan Lei used digital technology and the hands of others to paint the work Curators (image 75), a testimony to a group photograph of influential international curators in China.

image 75 Yan Lei The Curators, 2000, Acrylic on canvas, 133 x 290 cm

After 2000, an outstanding change within contemporary Chinese art occurred with the inception of curatorships and biennale systems in China. The rapid development of the contemporary art system brought tremendous momentum and capacity for artists to produce and exhibit art. Therefore, the beginning of the new millennium was a period when new artists, new creativity and new exhibitions flourished. Among them, the most active artistic inclination was experimental art. Either in the medium of installation, photography, video art, multi-media art or paintings, artists were constantly transcending themselves and existing artistic principles and rules in producing original artworks. Since 2003, those experimental artists who had stepped out of the travel-worn path marched into their creative heights, presenting the audience with a series of outstanding works. Sun Yuan & Peng Yu used bulldogs, tigers and boxing sportsmen in a series of performance installations, such as Dogs Which Cannot, Safety Island and Contend for Hegemony. Xu Zhen’s practical joke style work Earthquake disrupts usual viewing habits and Liu Wei’s work of 2004, Landscape (image 44) and Anti-material of 2006 emphasized the counterintuitive.

image 44 Liu Wei It Looks Like a Landscape, 2004, Color photo, 306 x 612 cm

Zheng Guogu used games to intervene in art exhibition system and social reality in My Home is Your Museum (image 87). All of these artists and their works shocked the art world both domestically and internationally. Chinese artists entered forbidden territories, crossed boundaries, and constantly pursued the possibilities of experimental art. Their efforts pushed forward and developed to discover a logic that was suitable to their own development. The Chinese mode, Chinese structure and Chinese characteristic of contemporary art also became critical issues that artists and curators focused on.

image 87 Zheng Guogu My Home is Your Museum, 2004, Mixed media installation, Dimensions variable

Young Chinese artists also began to frequently participate in international biennales and exhibit in foreign museums. Artists like Yang Fudong, Sun Yuan & Peng Yu, Cao Fei and others, in comparison to the older generation of artists from the 1980s, were offered more opportunities to exhibit abroad. Therefore, while they accumulated and digested their international experience, they also gained international vision and cultural strategy beyond their native country. Sun Yuan & Peng Yu’s Old Folks Home from 2007 (image 60) and Cao Fei’s RMB City from 2008 (image 14) are examples of artists demonstrating their unique cultural sensitivities in a globalizing context. Moreover, they express their understanding of the world on an international platform so they could reveal their own creative capacity with better precision.

image 60 Sun Yuan & Peng Yu Old People’s Home, 2007, Mixed media, 13 figures, Dimensions variable

image 14

Cao Fei RMB City,

2008 till completion, Full documentation of Second Life project: photos, videos, objects, digital data, Dimensions variable,

Unlike the generation from the 1990s, artists in the new millennium observed the “cultural revolution” sources from a distance. Through the artists’ reminiscence and attention to historical images, Jing Kewen’s Dream 2008 (image 35), Shao Yinong and Mu Chen’s The Assembly Hall–Xingguo Wenchang Temple (image 55), Wang Jianwei’s video My Visual Archive (image 98) and other artworks related to visual resources appropriated from the Cultural Revolution disclose mental conflicts on the incompatibility of the past with the rapid changes taken place in reality.

image 35 Jing Kewen Dream 2008. No.1 (Nurses), 2008, Oil on canvas, 250 x 350 cm (2 panels)

image 55

Shao Yinong & Mu Chen The Assembly Hall–Xingguo Wenchang Temple, 2002, Colour photo, 126 × 177 cm

image 98 Wang Jianwei My Vision Archive, 2002, 2 channels video, sound, color, 10 minutes 15 seconds, loop

Many young artists making works on paper or canvas have also bid farewell to the obvious impression of youth, shifting to discovering the development of conceptual painting rationally and proactively. Xie Nanxing’s Untitled (image 70) completed in 2000 is based on visual model of digital images.

image 70 Xie Nanxing Untitled (Flame), 2000, Oil on canvas, 220 x 380 cm

He enlarges the image proportionally in order to represent the illusory and misty impression of flames over a gas burner. His Picture of Voice I (image 71) seems to have been inspired by video clips of a car loading. T

image 71 Xie Nanxing Picture of voice I, 2001, Oil on canvas, 220 x 1140 cm (triptych)

image 71 Xie Nanxing Picture of voice I, 2001, Oil on canvas, 220 x 1140 cm (triptych)

he overall color tone and light variations from the car’s headlight are sufficient to offer blinding and dizzying visual impressions. Xie Nanxing’s pursuit of dual perfection for the overall imagery and its details sets a delicate trap for distinguishable everyday objects. It is easy for the audience to be lost in the momentary illusions of these images and these images allow them to experience and re-assess the visual significance of images. Without a doubt, oil painting is a medium in which Xie Nanxing explores visual experiences. Chen Wenbo, on the other hand, departs from the spotlight and mesmerizing highlights in urban landscapes and objects. He investigates the shadows of vanity and inspects the delusion and unbalanced psychology in people’s subconscious produced by these artificial objects. In his 2004 work Inflammable (image 19) revealed an unsettling psychological content embedded in our everyday experience. Chen Wenbo’s personal imagination is in fact a shared visual illusion that catalyzes a new aesthetic revolution.

image 19 Chen wenbo Inflammable, 2004, Acrylic on canvas, 240 x 340 cm

Beginning in 2005, the Chinese art market erupted. Commercial forces entered the art world in large scales both domestically and internationally. 798 Art District in Beijing became a site for hundreds of galleries, museums and art organizations. The Chinese art world in total, avant-garde art, official art, and commercial art, then entered an era of prosperity.

After 2006, many artists born in the 1970s and 1980s began to enter the main force of China’s experimental art. Most of them grew up under the impact of consumer society and globalization, when commercial violence replaced political and ideological pressure and became the nemesis for their creativity. They have built a value system based on their own life experiences. They are not only more keen on expressing the power of sensitivity and the resources from their bodies, but also reject the habits of setting the significance of the artworks as the primary goal. They have accumulated “practical” experiences through intense creativity and exhibitions, yet without avoiding self-criticism. Their constant discovery of the boundaries of art assures the potential for future prosperity of and talent in contemporary Chinese art. Qiu Xiaofei’s meticulous paintings on the nostalgic glass-fiber reinforced plastic furniture in his work Almost 7 O’clock (image 52), Hu Xiaoyuan’s A Keepsake I cannot Give Away (image 31), an enticing yet unfathomable image, Chu Yun’s Constellation (image 20) presenting a post-modern poetic imagery of the dispersed flickers in a room from electronic objects, or Qiu Anxiong’s animation In the Sky (image 96), the fantastical interchangeable relationship between men and nature, was all inspired by the context in which the artists grew up, offering experiences of defining cultural logic in different aspects and levels of contemporary Chinese art.

image 52 Qiu Xiaofei Almost 7 o’clock, 2005, Painted fiber-glass, Dimensions variable

image 31

Hu Xiaoyuan A Keepsake I Cannot Give Away, 2005, Mixed media installation (hair on silk), 20 pieces (diameter 17–30.5 cm)

image 20 Chu Yun Constellation No. 1, 2008, Mixed media installation, Dimensions variable

image 96 Qiu Anxiong In the Sky, Video, 8 minutes 12 seconds

For this new generation of artists, the hue of avant-garde in contemporary art is fading. Experimental art is only a work method of their everyday experience. In order to enter a framework of artistic and conceptual freedom, their creativity begins with resolving their own issues and completely discarding the ontological and methodological confusions of “making it or not” and “how to make it”. They are participants of shared cultural issues in China and the world, adopting active roles in their creativity, demonstrating a mature and long-term artistic phenomenon.

V. Curator’s Conclusion

The Sigg Collection comprises over 2000 pieces of contemporary Chinese art and is a material documentation of a continuous and systematic thread from 1971 to today. An archive of this kind is rare, either in China or in the world. Its essence exemplifies a unique cultural wealth. The narrative of contemporary Chinese art that I have followed in this essay is only one approach to link the artworks of the Sigg Collection. Due to the numerous facets of the collection, a chronological summary of portraying the most significant artworks in the Sigg Collection does not only incisively highlight its academic value, but also demonstrates its significance on the visual history of China of a particular era.

As a curator, my essay is a thematic discussion for the first Sigg Collection exhibition of the virtual online museum. It compliments and references 101 artworks. Neither the exhibition nor the essay is a full representation of the Sigg collection. However, based on the art historical thread of contemporary Chinese art, these 101 works are representative of the Sigg Collection.

My Essay is closely tied to the 101 artworks shown in the virtual museum. This is my effort of telling the history of contemporary Chinese art through images. Even though some works were not mentioned in this text, they are equally important. (English translation: Fiona He)